|

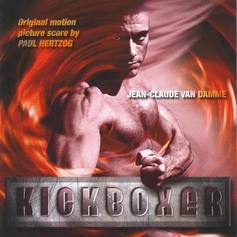

The following is from my liner notes for the Perseverance Records release of the score from Kickboxer:

In at least one way, Kickboxer was a film composer’s dream come true: I was hired before filming began. After I finished scoring Bloodsport, Mark DiSalle considered me part of his team and signed me up for Kickboxer early in the summer of 1988. He gave me a copy of the script at about the same time (the film was then entitled The White Warrior, I believe), and for over six months prior to receiving a final edit of the film, I played around with musical ideas and programmed a palette of synthesizer sounds that I felt would work well in the score. Many of these sounds came from my new Roland D-50 synthesizer. What I especially liked about that instrument was the fact that it contained both digital samples and analog-style synth sounds that I could stack, splice together, and spread about the stereo spectrum. I had become somewhat disillusioned with the one-dimensional synth sounds I used in scoring Bloodsport and was thrilled to be able to create some electronic sounds that to my ear had depth and character. Most of the cues in Kickboxer contain several of these D-50 sounds, including the shakuhachi sound, the wild noises that Kurt hears in Stone City, and most of the string-like pads. I asked Mark DiSalle to take me to Hong Kong and Thailand to watch the filming and get in some first-hand research, but he didn’t take my proposal seriously. (I didn’t really expect him to.) Late in 1988, with the filmmakers back from Asia, I began to see some rough-cut scenes in the editing room and later in more finished form at screening rooms. The film already showed lots of promise with great opportunity for music, so I was looking forward to getting my hands on the final cut. At one of the screenings, I ran into Michel Qissi, whom I had met when working on Bloodsport (he was one of Jean-Claude’s best friends as well as his training partner), and he asked me how I liked his performance in the film. I told him I hadn’t recognized him in the film and then felt pretty dumb when he told me he had played the role of Tong Po. I guess I hadn’t realized that a make-up artist could turn a North African into a Thai kickboxer. It wasn’t until early 1989 that I began composing to picture. I composed directly to the video, using a bank of synthesizers and a Roland MC-500 sequencer. Looking back from the 21st century, those gadgets from the 80’s seem like archaic dinosaurs, but at the time they worked well enough for me. In addition to the D-50, I used a Yamaha DX-7 and TX-7, an Oberheim OB-8, an early edition of the Ensoniq Mirage, and an Alesis HR-16 Drum Machine (which I spent hours with, tuning the multiple triangle sounds I used instead of a high hat on such cues as “The Eagle Lands” as well as the jungle-style drums in the final fight sequence). I believe I had about three weeks to compose, maybe four. I worked in a spare bedroom and put in approximately 18 hours a day seven days a week. I would start by watching a scene over and over, then start improvising to it, gradually decide on tempos, and begin sequencing drums and basic pads until I felt I had captured the essence of the mood I was looking for. Then I would record the basic tracks on a little portable 4-track cassette player and add enhancing sounds as I listened to the cue with the video. Most of the action cues I wrote directly on the sequencer, but I did write out on score paper those cues that I intended to add strings to, including the love scenes, the hospital scenes, “Ancient Voices,” “Buddha’s Eagle,” and “You’ve Done It Before.” Even though I had already developed the basic themes for the training sequences and the love scenes before the final edit was finished, fitting these ideas to picture required a great deal of rethinking. |

My approach to the film was varied. I treated the love scenes and non-fighting dramatic scenes much as film composers in Hollywood have always done. But the fight scenes and training scenes I thought of as something like ballet: a martial arts ballet. I tried consciously to make the music and the on-screen movements work together as dance, combining elements of rock and roll with my own interpretation of Asian music. And you might notice that the tempo of the ballet gradually speeds up as Kurt’s skills increase.

About two-thirds of the way through the score, Mark DiSalle came over and listened to what I had done. He liked most of it, but he wasn’t thrilled with one of my main sounds (a sample of a harp) and also asked me to rewrite part of one cue (the end of “Mylee is the Way”). I wasn’t entirely happy to rewrite a cue, but I must say that the rewritten version ended up sounding much better, and so I was glad Mark had given me his input. As for the harp, I changed its eq in such a way that it was much less strident, and doubled many of its solo lines with other instruments. I didn’t write the final fight sequence until the very end, since the editing was still going on as I composed to earlier reels. Mark was too busy to come up to the house when I was finally finished, so I took a cassette of the final cues down to the editing room in Hollywood and we listened on a boom box while the editor ran the film through one of those old-fashioned editing machines. Everyone liked the cues though they joked with me about how many drums I had used. For my part, I was particularly pleased with the sound I came up with for the primal music that underlies Tong Po’s initial success in the final fight: I spliced a sample of a piano’s initial attack to some very buzzy synth sounds that seemed to create this angry and primitive sound of evilness to my ear. With final approval from the boss, I moved into the recording studio. I literally moved. My engineer and I were happy working at Sound Affair in Costa Mesa, but unfortunately the studio was about a two-hour drive from my house. So I made a deal to stay at the home of the studio owner, Ron Leeper, while I recorded the score. Since the score was mainly synthesized, we laid down the synth tracks first. I added some live percussion, performed by one of my secret weapons, MB Gordy, and then overdubbed the violins. The rest was all pre-performed by me in the sequencer. I don’t remember how many days it took to record and mix, but it must have been a bit over a week. On the day we finished mixing, I handed the master tapes off to Cliff Kohlweck, my newly hired music editor, and went home to get some sleep. In short order we were on the sound stage in Burbank, doing the final sound mix for the film. Mixing can be a tense process, but for the most part the first time mixing Kickboxer went well. I say the first time, because after the mix was in the can and sent off to Germany for its first release date, Jean-Claude decided he wasn’t happy with the editing of the film, and so the film ended up being re-cut in a number of scenes. I was not particularly pleased that the music I had slaved over would either need cutting itself or else rewriting. In the end, we were able to cut the cues well enough to avoid rewriting and rerecording, but several cues did not work as well as they did in the original edit. If you can get hold of a German version of the film, you might see the way the cues originally worked. The biggest problems for me were with cuts made to “The Eagle Lands” (you will hear the full, original version here) and to the scene underscored by “Ancient Voices.” We didn’t actually cut “Ancient Voices,” but the film and music don’t line up as well as they originally did. The scene for one cue heard here, “Hospital,” was cut entirely from the film. Nonetheless, when I was at last able to see the final version of the film at the official screening, I was pleased with the results. I felt that I had captured the Asian flavor of the film, along with some of its mystery, ritual, and savagery. Given the relatively low budget I had to work with, I think the score works well and that it stands up to listening on its own. |