|

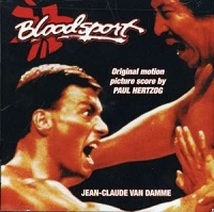

The following is taken from my liner notes for the Perseverance Records release of the score for Bloodsport:

Bloodsport was and is something of a miracle. I was told at the time that it was made for about $750,000. Internet sources suggest twice that. Even at the high end, I find it hard to believe that any film could be produced for such a slight budget, but given the miniscule pittance I was given to produce the score, I suppose the figure might well be true. Filming was done entirely in Hong Kong at the end of 1986, and certainly, filming outside the U.S. helped keep the budget down. Jean Claude Van Damme was still an unknown trying to get any work he could, so his fee must not have been a budget breaker. The producer was unknown, working on his first feature film. The director had been Peckinpah’s assistant director, not known for his own directing. And the other talent all came through the Cannon low-budget system, again keeping costs in line. So I guess that figure might indeed have been plausible. I first heard about Bloodsport through a friend who had edited a children’s video for producer Mark DiSalle and who had brought me in to rescue that children’s project when its first score was rejected. I stayed awake for two days and nights and completed a new score that Mark was very pleased with. So when Mark returned from Hong Kong with Bloodsport in the can, I called him to tell him I’d be interested in scoring it. He was noncommittal, but invited me to a screening of the rough edit some time in the winter of 1987, February or March. I sat in the Cannon screening room with Mark and director Newt Arnold, enjoying the film and wondering what sort of song and dance I could perform to get the job. Then at the end of the screening, Mark told me the job was mine. No negotiations. No song and dance. Cannon would pay such and such. Take it or leave it. Well, I certainly took it. Feature films don’t come quite so easily to most unknown composers. I got a final edit sometime in March and a deadline of April 27th to deliver the recorded score. I sat in my little rented guesthouse in the San Fernando Valley with a Roland MC-500 sequencer, an Oberheim DMX drum machine, a Yamaha DX-7 and TX-7, an Oberheim OB-8, and an Ensoniq Mirage sampler and went to work. I had a vague idea what to do, having scored parts of two films previously, the first one composed with a couple of partners, the second one adding only 20 minutes of forgettable sequenced drivel. I had studied film scoring with Don Ray at the UCLA Extension. I knew my harmony and |

counterpoint. I had played in pop/rock bands for a good fifteen years. So off I went.

I entered the studio on April 13, 1987, with a little over an hour’s worth of cues digitally recorded into the sequencer. My engineer and I got the synthesizer parts recorded onto wide tape and then I added a ton of live percussion, performed by M.B. Gordy and Denny Fongheiser. I added some Chinese harp performed by Jamii Szmadzinski. I also recorded the two songs (written with my old friend Shandi) “Fight to Survive” and “On My Own—Alone” with vocals by Stan Bush and some guitar work by Tim Pierce. I still have the studio bill, and between April 13th and April 23rd, we spent 133 hours recording and mixing. But we finished and delivered the score on time and with a minor amount of the budget left for me to feel that I could pay myself a little. Shortly thereafter, (perhaps the next day?) I found myself on the sound stage watching the fascinating process of mixing the final sound for the film. I had never actually witnessed a film mix, and I was quite amazed at all the sound elements (dialogue live and dubbed, location sound effects, added sound effects, foley) that had to be scrutinized and premixed before the music could be considered. We spent about a week, a very intense week, mixing. And then, with the film completed, the energy expended, nothing. Cannon sat on it. For nearly a year, nothing happened. Apparently Cannon didn’t believe in it. Finally in the final weekend of February, 1988, the film was released in only 5 western states. I suppose it was a token release to satisfy some sort of contractual obligations. But now the miracle started happening. Even in its limited 5-state release, the film charted in the top twenty nationwide. (Well, it was only 19, but hey, it was on the charts.) By its sixth weekend, still in regional release, it had managed to remain in the top 40 and earn over $2,000,000. Not bad for a film made for somewhere around half that amount and released in only five states. So finally Cannon went nationwide, and the film jumped to number 10 the last weekend of April and to number 7 the first weekend of May. The largest number of screens it ever played on was 784. The first weekend of May, Bloodsport was number two in box office receipts in New York City, averaging $4,546 per screen on 88 screens. By June 1, the last weekend I kept clippings for, the film had grossed $10,808,163. Not so shabby for a film Cannon didn’t even seem to want to release. And Jean Claude Van Damme was now a star. Then, the next year more miracles started happening. The film came out in Germany, peaking at #5, followed by France, peaking at #3, and other European countries. I heard rumors that it was the highest-grossing film in the history of the Philippines. It just kept going around the world making money for someone (not me). And then it started playing on cable tv in America and around the world, and I finally did begin to see some royalties. And today, nearly 20 years after writing this score, I can report that Bloodsport remains as popular on tv around the world as ever. Who knew? |